100 Years Ago, A U.S. Pilot Saw An ‘End To The Sorrow’ On Armistice Day

Listen

BY DINA KESBEH & JAMES DOUBEK

One hundred years ago, Nov. 11, 1918, the Allies of World War I and Germany agreed to a cease-fire signifying the end of the “war to end all wars.”

Representatives of the two sides signed the agreement in Compiègne Forest, in northern France, on the day of the year now recognized as Armistice Day.

It came into effect at 11 a.m. French time: “the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month.”

Fenton Caldwell was in France that day, too — or, technically, over it. Hundreds of miles to the south, near Bordeaux.

“I was at about 10,000 feet in the air, flying a De Havilland DH-4 airplane,” the Army Air Corps pilot told his family in 1975. He was on a reconnaissance mission, unaware that the armistice had begun.

Caldwell’s family recorded his memories 57 years later. His niece, Joy Panagides, shared her family’s audio treasure with NPR.

“Uncle Fenton was my favorite uncle, he had wonderful stories,” Panagides tells NPR’s Lulu Garcia-Navarro. “He enchanted everybody in the family with his very good memory for details.”

Interview Highlights

On what happened when he was flying over Bordeaux

He was looking at where there might be enemy installations, where there might be any evidence of firing of guns — different places, so that this could be reported back to their base.

The way they got information from home base was somebody would lay out sheets, white sheets, on the ground. The airplane didn’t have any kind of radio contact with him so these pieces of white cloth were laid out on the ground with a code that meant something.

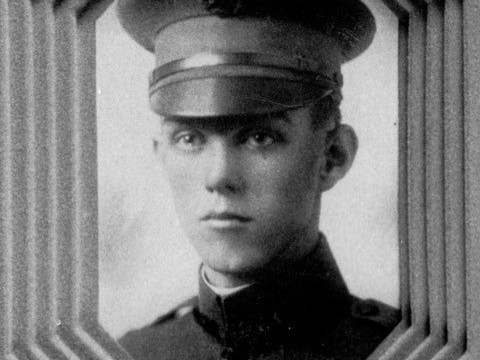

Joy Panagides says her uncle Fenton Caldwell “was my favorite uncle, he had wonderful stories. He enchanted everybody in the family with his very good memory for details.” CREDIT: Cameron Pollack/NPR

And that wasn’t happening. They didn’t know why.

So he flew a little bit more with his colleague and, nothing, they didn’t see anything. And then he understood that he didn’t have as much gas as he thought he did and recognized that he would have to land.

And it was too far to get back to his home base. So he looked for a field where he could get down. …

People that should have been coming out, because it was an American plane on a French field, they didn’t come out to see who it was and why they were down.

And when they got out of the plane, again, nobody was there, to check on, see what was up. So they had to walk along, past some of the buildings. And all of a sudden, they could hear some big party going on down the way and that’s how they discovered la guerre est finie [the war is finished].

On processing World War I

All during this time he had problems as they all did with staying alive. The plane that he was in mostly the DH-4, a De Havilland, was a very precarious airplane and was known as the “fiery coffin” because of the problems with the fuel line. It would either explode or let go and people were falling to their deaths.

[It was] incredibly dangerous.

That was one of the problems, the other one was because they were doing reconnaissance flights they were targets for the enemy.

On what Caldwell said Armistice Day meant to him

I do have a piece that’s from him that I’d like to just say, because he realized that Americans had different meanings for Armistice Day. But for him the most important part was that, he says, “now I was free from that ever-present conscious or unconscious knowledge that there was a chance of not living another day, the end to the sorrow of seeing close friends go down, some in flames and to those funerals I had gone with heavy heart to stand at attention during the firing of rifles and the hearing of the mournful notes of Taps.”

So he was incredibly encouraged and grateful I would say, this was important.

NPR’s Ned Wharton and Joanne Levine produced and edited the audio version of this story.

Related Stories:

Getting To Know Logan Wheeler, A Washington State Veteran And Alum Who Died A Century Ago

Sometimes we grieve for people we’ve never met. Walking through a cemetery, looking at the graves of people who exist to you only as names in stone, it’s easy to wonder at the loss. It’s a shallow grief, not the long-term grief for a friend lost, but the fleeting interjection of some unknowable person into your periphery.

100 Years Ago, A U.S. Pilot Saw An ‘End To The Sorrow’ On Armistice Day

Fenton Caldwell was a reconnaissance pilot who was flying over France on Armistice Day, Nov. 11, 1918. His niece, Joy Panagides, shared an audio recording of his memories of the day.