Idaho Health Board Meeting Stopped After ‘Intense Protest’ From Anti-Mask Crowd

READ ON

BY REBECCA BOONE / AP

Idaho public health officials abruptly ended a meeting Tuesday after the Boise mayor and chief of police said intense protests outside the health department building — as well as outside some health officials’ homes — were threatening public safety.

The request from Boise Mayor Lauren McLean and the Boise Police Department came just a few minutes after one health board member, Ada County Commissioner Diana Lachiondo, tearfully interrupted the online meeting to say she had to rush home from work to be with her son. The board had been expected to vote on a four-county mask mandate in Idaho’s most populated region.

“My 12-year-old son is home alone right now and there are protestors banging outside the door,” Lachiondo said.

Another board member, family physician Dr. Ted Epperly, said protests were “not under control at my house,” as well. Protesters went to at least three board members’ homes, the Boise Police Department said.

SEE MORE: Coronavirus News, Updates, Resources From NWPB

Hundreds of protesters gathered at the Central District Health parking lot before and during the meeting. The protest at the health building was organized, at least in part, by a loose multi-state group called People’s Rights. The group was created by Ammon Bundy, an outspoken opponent of mask mandates during the coronavirus pandemic who gained national attention and stoked the so-called “patriot movement” after leading armed standoffs at his father’s Nevada ranch in 2014 and at a wildlife refuge in eastern Oregon in 2016. Members of an anti-vaccination group called Health Freedom Idaho also attended the protest. It wasn’t immediately known if Bundy attended the Boise protests Tuesday evening.

Other groups are supportive of the proposed mask rule. An organization called the “Pandemic Committee” gathered supportive messages from 600 area residents, putting them on yard signs delivered to the health district building several hours before the meeting was scheduled to begin.

RELATED: He Lived Near Idaho, With Fewer COVID Restrictions. Now He’s Dead

Central District Health Director Russ Duke interrupted the Tuesday meeting to inform board members of the mayor’s request.

“I got a call from the mayor, and it sounds like the police, and she is requesting that we stop the meeting at this time because of the intense level of protesters in the parking lot and concern for police safety and staff safety as well as the protesters that are at some of our board members’ homes right now,” Duke said.

The Boise Police Department later issued a statement on Twitter that said they requested the meeting adjourn “in the interest of public safety.”

“Our first priority is to maintain safety and public order. Officers are currently monitoring the crowd and responding to reports of additional incidents in the city,” the department wrote.

Police arrested one woman at the Central District Health building after officers said she refused to follow CDH rules. The police department also released a statement saying officers were seeking arrest warrants on suspicion of disturbing the peace for some of the protesters who went to board members’ homes.

Supporters of health workers and mask mandates held a silent counter protest by decorating their vehicles at an anti-mask protest at the Central District Health offices, Tuesday, Dec. 8, 2020 in Boise, Idaho. CREDIT: Darin Oswald/Idaho Statesman via AP

Video uploaded to Facebook by one of the protesters outside of Lachiondo’s home showed a small group of armed protesters banging on buckets, using air horns, playing loud siren and other noises and screaming on the sidewalk.

Lachiondo later posted a statement on her Twitter account, saying her family was fine and thanking the police for their help.

After the health board meeting, McLean issued a statement condemning what she said was a group of disruptive outsiders seeking to divide the Boise community.

“Our local health board is being asked to make decisions at the local level in lieu of statewide action,” McLean wrote. “And when taking this job seriously — doing everything they can to help address the spread of COVID, they’re threatened and intimidated. No child should be frightened by a mob of protesters, no local official should fear violence for their public service.”

Idaho Gov. Brad Little has repeatedly urged Idahoans to wear masks but has declined to issue a statewide mask mandate, instead leaving that decision in the hands of the regional health boards. He condemned the protestors’ actions at the board members’ homes.

“The actions of protestors at the private residences of public officials is reprehensible. It is nothing more than a bullying tactic that seeks to silence. Our right to free speech should not be used to intimidate and scare others,” Little wrote on his Twitter page. “There is no place for this behavior in Idaho. I urge calm among Idahoans so we can get through the pandemic together, stronger.”

The governor declined to answer Tuesday evening when The Associated Press asked if he still felt it was appropriate to leave contentious decisions on mask mandates in the hands of the local boards, which are made up largely of non-medical professionals.

Instead, Little’s spokeswoman Emily Callihan said Little “will continue to support those local leaders who, in consultation with medical experts, make tough decisions to protect our citizens against COVID-19.”

She also pointed out the governor’s statewide orders that require physical distancing at gatherings, limit public and private gatherings to 10 people (except for religious or political events), require patrons to be seated at bars and restaurants and require masks at long term-care facilities.

Last week, regional hospital officials warned that they were so overwhelmed by high numbers of coronavirus patients — and by health care staffers unable to work because they are sick — that the state could be forced to implement “crisis standards of care” within the next month. Crisis standards of care are designed to ensure that the patients most likely to survive COVID-19 are given access to potentially life-saving treatment when there isn’t enough to go around.

The Idaho Department of Health and Welfare reports that at least 113,905 Idaho residents have been infected with the virus so far, including 2,012 new cases reported on Tuesday. So far at least 1,074 residents have died from COVID-19.

The draft mask order is designed to slow the spread of the virus so that the health care system isn’t overwhelmed. If approved, the order would allow youth and adult sports to continue, and would allow visits to long-term care facilities in some situations. Failing to comply with the mask mandate would result in a misdemeanor, but it includes exceptions for those who have trouble breathing, young children and others.

Copyright 2020 Associated Press

Related Stories:

Health district secures grant funds, distributes response survey after Lineage warehouse fire

Fire crews spray water on rubble at the Lineage Logistics fire in Finley, Washington. The fire started on April 21. (Credit: Benton County Fire District 1) watch Listen (Runtime 1:08)

Medication first, and then a whole-health approach

A couple of blocks off U.S. Route 12 in Walla Walla, Blue Mountain Heart to Heart has been treating people with substance use disorder for over a decade. But, for years, the nonprofit was unable to quickly offer a proven treatment for opioid use disorder: medication-assisted treatment.

Staffers would have to arrange for patients to get an assessment with a trained substance use professional elsewhere to start the medication. Getting that assessment, and then, getting started on the medication, buprenorphine, used to take weeks.

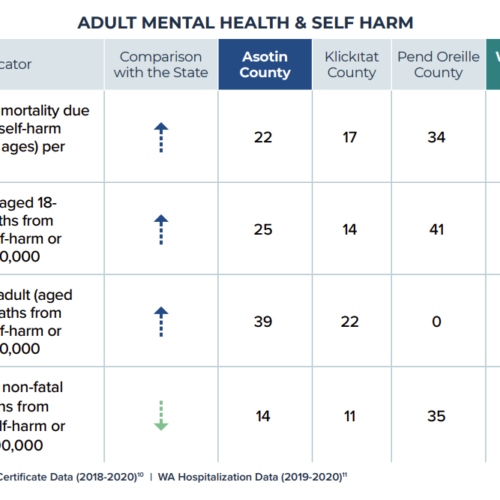

Asotin County assessment shows needs in mental health, housing, substance use treatment

An assessment by the Asotin County Health District shows that mental health, housing and aging in place, along with substance use, are some of the largest health issues facing the community.