Remembering Julian Bream, The Classical Guitar Giant With The Soul Of A Jazz Player

BY TOM COLE

Andres Segovia popularized the classical guitar. Julian Bream took it to the next level.

Bream, who died Aug. 14 at the age of 87 in his native England, stepped into a guitar world in which everything had to be done just so … and didn’t do it that way. By the time he was a teenager, Bream was asking contemporary composers to write for him. He took an old lute his father bought from a sailor for 2 quid and went on to help revive interest in the instrument and play an important role in launching the early music movement. But again, he didn’t do it quite the way he was supposed to.

He was a Cockney, born in Battersea in central London on July 15, 1933. His family moved to the suburb of Hampton when he was 18 months old. It wasn’t always an easy childhood: He and his younger sister were evacuated twice to the countryside during the Blitz and the family struggled financially.

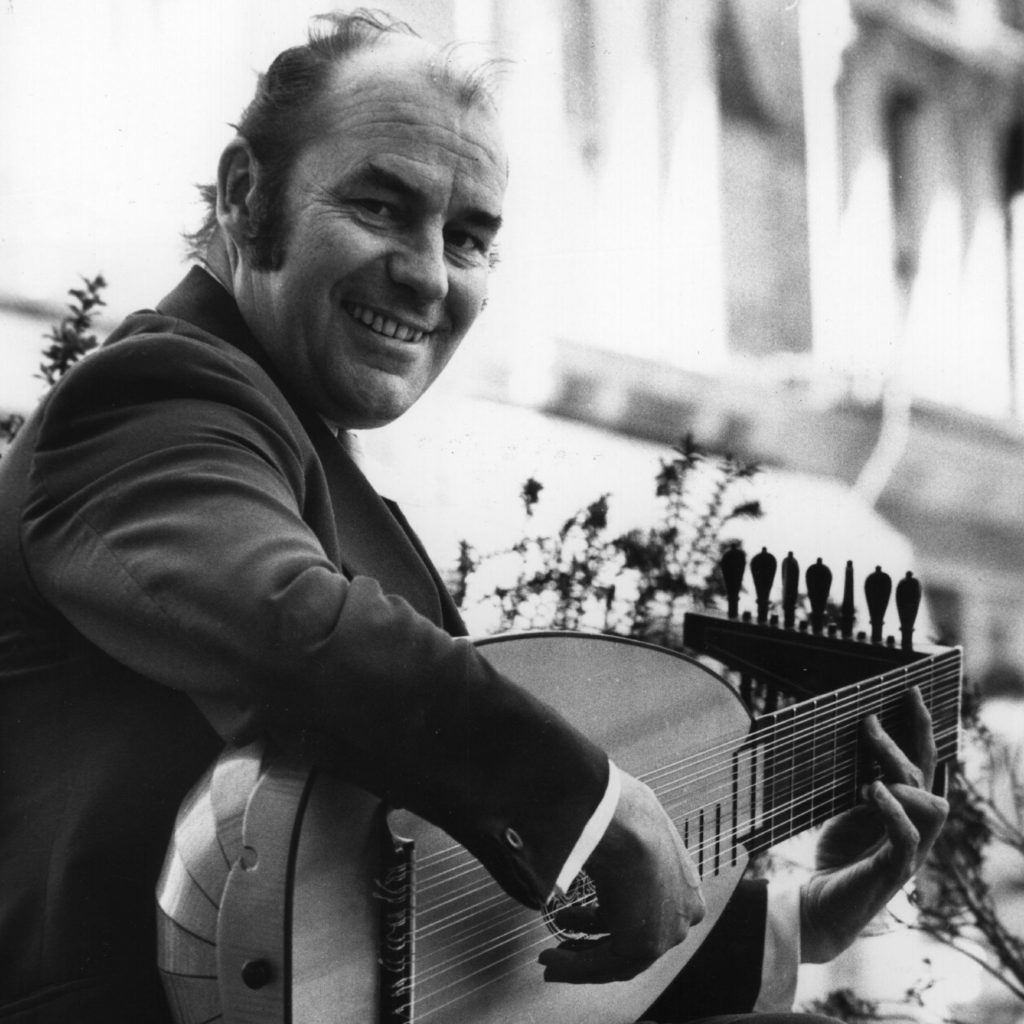

English guitarist and lutenist Julian Bream. CREDIT: Evening Standard/Getty Images

Yet his father was a talented commercial artist and, as Julian said in the excellent 2003 documentary, My Life in Music, “a natural musician.” Henry Bream led an amateur dance band and it was his Django Reinhardt 78s that drew Julian to the guitar. His father also had a book of fingerboard harmony by the great early jazz guitarist Eddie Lang; that became young Julian’s first guide. He would go to his father’s gigs, sit behind the curtain and play along.

His father bought him a classical guitar for his 11th birthday and the two learned together, playing duets. Later that same year, Henry brought home a Segovia 78 and that was it for both of them. Segovia even offered to teach young Julian at one point but, for one reason or another, it never happened.

On July 17, 1948, Julian made his London debut at Alliance Hall (not the more prestigious Wigmore, as is often reported). The stage was so low, he had to perform with his chair up on a table. The Times and the Daily Mail praised his performance but panned the hall.

That same year, his father was deep in debt and his parents separated. Julian and his sister moved in with their father. It was hard for the young musician, as he says in the documentary: “Music has been my real solace. And that’s why I play music. And that’s why I’m so determined, or have been so determined to pursue what I wanted to do, come what may.”

All the while, Julian had been studying piano (since he was 10) and along the way, even picked up the cello. He was admitted to the Royal College of Music, tuition-free, at the age of 16, to study piano and composition — the school didn’t have a guitar program. In fact, he was forbidden to bring his guitar on campus. He eventually quit.

But he learned something there that was to guide him for the rest of his career, as he said in the documentary: “To present pieces in their entirety. Like a whole Bach suite … I found that the Segovia programs, with their delicious morsels, where he’d take the smash hits from the E minor Lute Suite or something like that, rather unsatisfactory because you would just be getting a lot of meringues and lollipops instead of meat and potatoes, you know. And I have always been a meat and potatoes man. And I’m a great believer in making up programs so there is something for not only me, but the audience to get their teeth into.”

It was also at this time that he had another revelation. He’d been invited to play guitar in a stage production of Othello, directed by Kenneth Tynan. Bream went to the library to look for music that might be appropriate for the production and discovered a collection of pieces by John Dowland, the great Renaissance composer and lutenist. Bream took that lute his father had bought, which was strung like a guitar, had it reworked into a proper lute and embarked on a second path that would prove as important as his commissioning of works by contemporary composers: the revival of interest in centuries-old music and taking it to a mainstream audience with the Julian Bream Consort.

It was back to jazz in 1952 when Bream had to fulfill his national service. After a brutal stint in an artillery unit, which he described as “awful,” he landed in an army dance band. He bought an Epiphone electric guitar and was swinging again.

When he got out, he resumed his concert career. He met and became friends with a giant of 20th century music, composer Benjamin Britten and his partner, the acclaimed tenor, Peter Pears. Britten would later write a masterpiece for Bream: “Nocturnal after Dowland,” based on John Dowland’s “Come Heavy Sleep,” a piece that Bream and Pears recorded on one of their collaborations.

Bream commissioned works from some of the greatest composers of his time: Hans Werner Henze, William Walton, Michael Tippett, Toru Takemitsu and Malcolm Arnold, to name just a few.

He toured the world and was a regular on BBC radio and TV. There are some revealing excerpts in the Bream documentary, My Life in Music. One, an obviously staged “jam session,” shows Bream and some “friends from the pub” jamming on a Quintet of the Hot Club of France-style tune with the guitarist ripping into a Reinhardt-esque lead — fingerstyle on a nylon-string, bending notes with power and passion and an ear-to-ear grin at the end.

“I love playing jazz because I love the freedom you have to improvise,” Bream says in the documentary. “It has given me a feeling in my classical repertoire of creating the atmosphere of the here and now. Just the spark of a moment that can come from hitting a note with a certain color that you’ve never hit it before or giving another note an extra vibrato or by just accentuation or articulation. And if you can keep that ability to be alive to now, then I think that is a precious commodity for an artist.”

In another BBC excerpt, Bream talks about going to India in 1963 to “replenish his spirit.” And it again shows him improvising with two masters of Hindustani classical music, tabla player Alla Rakha and sarod virtuoso Ali Akbar Khan, of whom Bream says in the documentary, “He seemed to me just about the finest musician I’ve ever met in my life … His improvisations were so interesting, so fluid, so inventive, so evocative, so exciting that I thought, ‘This is the way to play music.’ Not write all this damn stuff out and get the tempo right and the metronome speed correct, you know. This was the way to make music! Just sit down and do it.”

And that’s just what Bream seemed to do in his classical pieces as well. To watch him play, he’s all in: his upper torso in motion, swaying to the music; his head bobbing; eyebrows arching; eyes squeezed shut. But his mouth is the giveaway. If you’ve ever watched a jazz guitarist on stage, they do the most remarkable things with their mouths: scrunching them up, twisting them, opening and closing them. The tongue will even poke out every now and then. They’re so into it, they have no idea how expressive their faces are.

Julian Bream was into it. And he named his dog Django.