Good Thinking: How Rodin Ensured The Financial Future Of His Paris Museum

LISTEN

BY REBECCA ROSMAN

Museums around the world are struggling because of the coronavirus: New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art is projecting $100 million in losses this year, and even France’s publicly funded Louvre has lost 40 million euros following a four-month closure.

Musée Rodin in the southwest corner of Paris has a unique economic model to keep it running … and it involves selling some of the artwork.

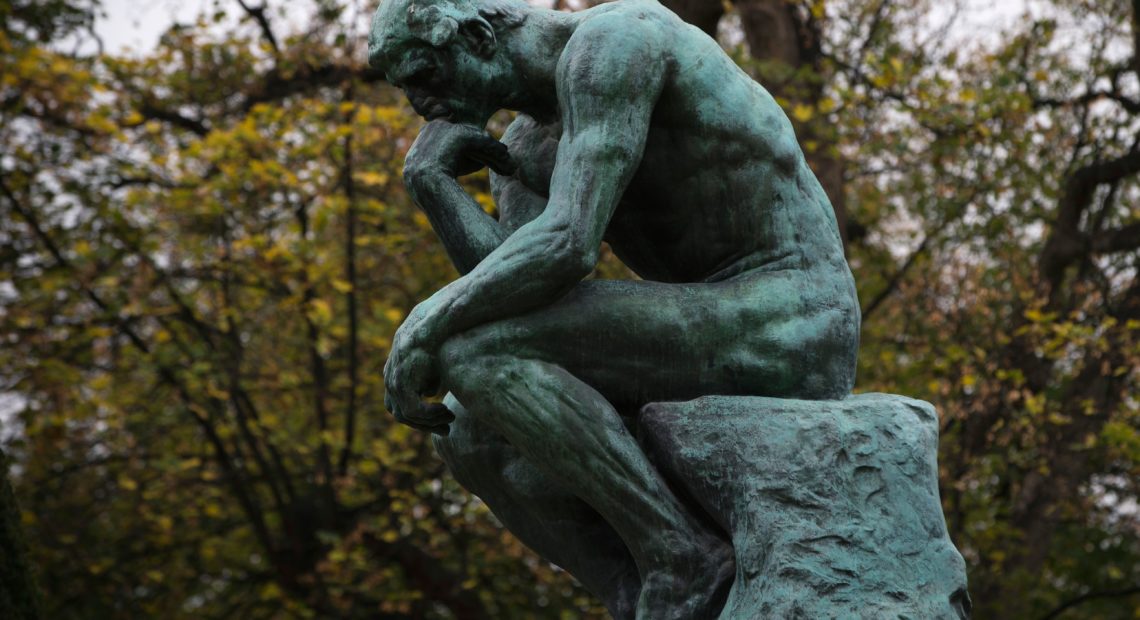

The 19th-century sculptor’s most famous bronze statue, The Thinker, sits amid pink and white roses in a spacious hedge lined garden, with the Eiffel Tower in the distance. If you recall seeing The Thinker elsewhere, you’re right. Thanks to Rodin’s economic ingenuity, this statue and many of his others also can be found in galleries around the world.

The Rodin Museum in Paris is selling sculptures to pay the bills — and that’s exactly as the artist intended. When he died in 1917, Auguste Rodin left the museum plaster casts for just this purpose. Above, The Thinker (Le Penseur) is pictured ahead of the Musée Rodin’s reopening in November 2015.

CREDIT: Joel Saget/AFP via Getty Images

When he died in 1917, Rodin left his estate to the museum, including the original plaster molds of more than 100 sculptures. “Rodin gave the economical system so that the museum could live,” museum communications director Clémence Goldberger explains.

The museum still uses these molds to recast new bronze sculptures and sell them — and with a projected loss of 3 million euros this year, the molds have never proved more valuable.

Just don’t go calling what they produce copies.

“Legally they are originals,” says Didier Rykner, an art historian and founder of the website La Tribune de L’Art. “But you know, they are originals from Rodin and they were made one year ago — so what is original and what is not? ”

Rykner acknowledges the existential questions that arise from this practice, but says you can’t blame the museum for utilizing a system the artist himself put in place.

“It’s good because it brings money for the museum,” Rykner says.

There is a cap on editions — 12 per mold forever — so they maintain their rare value.

With prices starting at around 30,000 euros and extending to tens of millions, the molds have become a crucial safety net.

Even though the Rodin museum is considered public, it doesn’t take any money from the state. But that’s exactly what the artist wanted, says the museum’s director Catherine Chevillot.

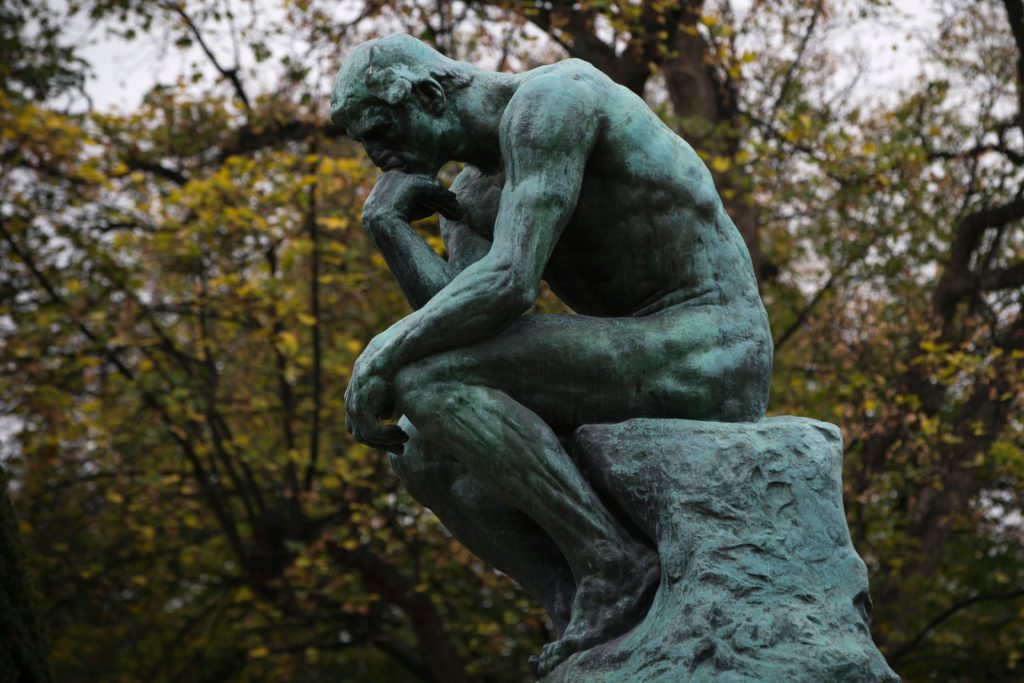

A visitor looks at Rodin’s The Thinker at Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin in May 2020. CREDIT: John Macdougall/AFP via Getty Images

“I think he wanted to be sure that his museum could survive and could be independent,” Chevillot explains.

After a four-month closure due to the coronavirus, the museum reopened to the public in early July. But the experience is different: There’s a face mask requirement, a hand sanitizer machine at the entrance and a one-way path through the galleries.

The most noticeable change, however, is the drop in visitors. The majority of ticket sales usually come from international tourists, many of whom are still barred from entry into the European Union.

On the top of that list are Americans, who made up a quarter of all visitors last year. “At the very beginning, Rodin was considered a bit too sensual for some Puritan spirits,” Goldberger says of the American appetite for Rodin, but that’s no longer the case.

Even if the Rodin museum in Paris won’t be seeing many visitors from abroad any time soon, fans may still be able to find “original” editions of the artist’s work in museums closer to home.

9(MDAyOTk4OTc0MDEyNzcxNDIzMTZjM2E3Zg004))