Areas Of The Northwest From Walla Walla To Umatilla To The Palouse Deal With Flooding, High Water

Listen

BY ANNA KING, DONALD ORR & SCOTT LEADINGHAM

UPDATED Feb. 8, 2020, 12:20 p.m.

Washington Gov. Jay Inslee has issued an emergency proclamation for 20 counties as major flooding inundated Washington and Oregon.

The original proclamation of 19 counties in western Washington was updated Wednesday to include Walla Walla County in southeastern Washington.

Heavy rain and melting snowpack have turned creeks into torrents, forcing the evacuations of communities and livestock across both Oregon and Washington. On the reservation of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla in northeastern Oregon, tribal spokeswoman Jiselle Halfmoon says emergency crews are going house to house.

“They’re making sure they have their water, food, shelter is adequate or to make sure they don’t need to be removed from their homes,” Halfmoon said.

In a statement released late Friday night, the Umatilla County Sheriff’s Office said county residents are advised to assess their resources and determine whether they are able to shelter in place for several weeks.

According to the evacuation notice from the UCSO, people should act fast.

“You are advised to LEAVE IMMEDIATELY! Gather any belonging and make efforts to protect your home. If you stay, emergency services may not be available to assist you further,” the statement reads.

Rescue crews will be on the ground and in the air by helicopter Saturday to attempt to make contact with residents. Officials said this will be the last evacuation notice residents will receive.

Emergency responders in northeastern Oregon responded Thursday and Friday, Feb. 6 and 7, to flooding around Umatilla, Oregon, and the reservation of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla. CREDIT: Megan Van Pelt / Confederated Umatilla Journal

“Today’s priority is search and rescue, trying to get out to those areas that are cut off. [I]f they’re able to shelter in place for several weeks they’re welcome to stay, but we’re really encouraging people to evacuate,” said Kevin Jeffries with the Oregon Office of Emergency Management.

As of Saturday morning, Jeffries said there were no assurances helicopters would be available for evacuation on Sunday or next week.

“Make that determination quick whether you’re going to stay or go, but today might be your last day to get out,” Jeffries said.

The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation also declared a state of emergency Friday. The CTUIR is advising residents of the reservation in need of emergency assistance to Umatilla Tribal Dispatch at 541-278-0550.

In Pendleton, Ore., the levy behind the East Oregonian newspaper was leaking Thursday night. About three feet of water came into the newspaper’s brick guesthouse basement, and it also inundated the businesses’ parking lot and newspaper loading dock.

The Umatilla River is starting to minorly erode away at Orchard Ave just outside Hermiston. #orwx #weather #flood @NWSPendleton pic.twitter.com/jcGCA4V6UT

— Mark Ingalls (@markaingalls) February 8, 2020

“We ended up printing, and getting the papers out the door,” said Kathryn Brown, an owner of EO Media Group. “The flooding has left a muddy film everywhere. Our loading dock looks like a muddy swimming hole. But we’re fortunate that it wasn’t any worse.”

Multiple roads and bridges are closed in both states. At least two sections of major east-west Interstate 84 are closed in Oregon.

On The Palouse

Residents in the Palouse region of southeastern Washington and north-central Idaho were also dealing with increased flooding risk Thursday and Friday. Though the National Weather Service had initially downgraded a flood warning for Paradise Creek through Moscow, Idaho and Pullman, Washington Thursday night into Friday, more rain on Friday caused new warnings.

As of 11 p.m. Friday, Paradise Creek in Moscow had reached flood stage of 9.2 feet.

But forecasters said Saturday morning that the creek had crested, and that water levels were expected to fall throughout the day.

River levels have crested on Paradise Creek in Moscow, ID. We expect the levels to continue falling through the day and flooding is no longer expected. #idwx pic.twitter.com/jOxDkodiwL

— NWS Spokane (@NWSSpokane) February 8, 2020

Paradise Creek is one of many water bodies that have risen over the past week. It runs through Moscow, across the border to Pullman, and dumps into the South Fork of the Palouse River. Its status in Moscow is considered a leading indicator of what could happen downstream in Pullman.

In Moscow, city officials warned residents to steer clear of certain roads and bridges with high water underneath, and to not drive through areas with water over the roadway.

A self-serve sandbag-filling station was also available to Moscow residents at 650 North Van Buren Street.

Missouri Flat Creek in Pullman, Washington, on Friday, Feb. 7, 2020. In April 2019, the same creek flooded its banks and overtook the road above, sending cars crashing into nearby buildings. CREDIT: Scott Leadingham/NWPB

Kevin Gardes, Pullman’s public works director, said earlier on Friday that the city had crews on 24-hour alert Thursday night. They also deployed sandbags and last week set up a plywood flood wall downtown. But crews are optimistic given the upcoming forecast.

“Looking out at the forecast for rain and precip for the next week or so, it looks like things should calm down a little bit,” Gardes said. “And that’ll allow time for some of the water to get out of the watershed. And the river levels will start dropping.

Pullman officials are understandably cautious when it comes to preparing for floods. Last April, a flash flood turned Grand Avenue into a river channel as Missouri Flat Creek overflowed – pushing cars into businesses and stranding people inside.

Gardes said the city learned from that incident and updated how they prepare and respond – including coordinating with their counterparts across the border in Moscow.

Anna King is a correspondent for the public radio Northwest News Network. Donald Orr is a reporter for Oregon Public Broadcasting. Scott Leadingham is news manager for Northwest Public Broadcasting.

Related Stories:

Why do atmospheric rivers hit some areas more than others?

Rain, flooding, storms – all pretty standard for Western Washington, but sometimes weather patterns spare some areas that have flooded before.

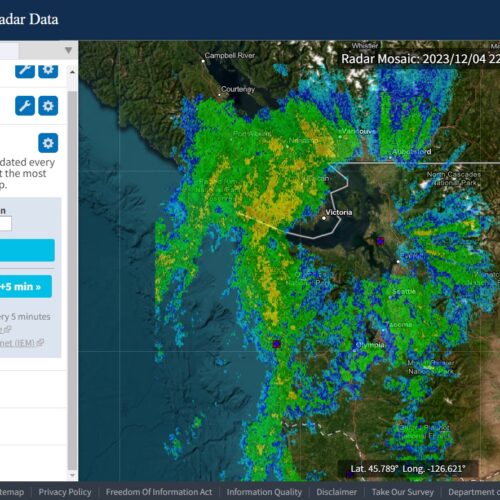

That was the case at the beginning of December, when Western Washington got so much rain that it caused flooding from the Stillaguamish River to the town of Rosburg.

New flood management plan considers more flooding types

After about five years in the works, the Pierce County Council adopted a new Comprehensive Flood Hazard Management Plan that broadens the scope of what kinds of flooding the county will plan for – from coastal to urban flooding.

Angela Angove is the floodplain and watershed services manager with Pierce County Planning and Public Works. She said different types of flooding are top of mind for people in the county, recalling the King Tides that caused tidal flooding last December.

The immediate impact of levee setbacks in Pierce County

In the foothills of Mt. Rainier runs the Carbon, the Puyallup and the White Rivers, meandering through towns and cities, along roadways and near homes, the paint strokes of the natural environment now surrounded by a human-built ecosystem. Once tightly restricted by levees, these rivers are beginning to again flow closer to how they would have, not adhering to the confines and rules of where humans want water to go.