‘I Write To Understand What I Think’: A Veteran Turns To Words After War

LISTEN

BY MARY LOUISE KELLY

Two weeks into the fight for Fallujah, Elliot Ackerman’s company commander told him he was both the luckiest and the unluckiest lieutenant he’d ever met. The luckiest — because right out of the gate, Ackerman was in the thick of the biggest battle the Marine Corps had experienced in decades. And the unluckiest — because everything he ever did after that would seem inconsequential.

That was back in 2004. Ackerman eventually served five tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, duty for which he was awarded the Silver Star, the Bronze Star for Valor and the Purple Heart. As it turned out, his commander was kind of right. Ackerman writes about his wars — and the years he has spent trying to make sense of the wider wars and turmoil in the Mideast — in his new memoir, Places and Names.

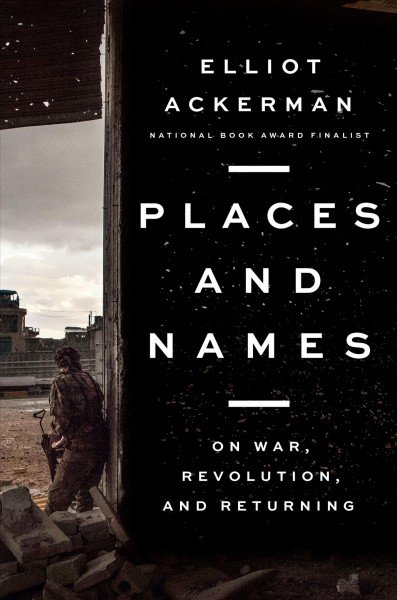

Places and Names:

On War, Revolution, and Returning

by Elliot Ackerman

“I was drawn back to wanting to have an experience that would be as meaningful as ones that I had had before,” Ackerman explains. “I had always felt — and still feel — like I want to have a life driven by purpose. My purpose evolved into being a writer.”

Interview Highlights

On understanding the ongoing conflicts in the Middle East as “all one war”

Whatever we announced in Iraq when we left in 2011 … it’s still not over today as we’re sitting here. It is still playing out. And one of the things that’s been difficult, I think, for my generation of veterans is that because the wars haven’t ended, every single one of us who’ve left the war have had to basically make a separate peace … [to] say, “You know what? I’ve done my last deployment. I know other people are going to continue to be deploying but I’m finished.” …

It’s basically deciding that you’ve finished your time — you’re not going to reenlist, or if you’re an officer you’re going to resign your commission, and you’ve decided that you are going to move on. …

Every single one of us has had to look at someone we know and care about and say, “I know you’re going on the next deployment but I’m not. I’m done.” And declaring that separate peace I think can be very, very complicated. I know it was complicated for me.

On making sense of his combat experience by writing fiction and nonfiction

I write to understand what I think. So if you look in this memoir, a lot of it is grappling with what these experiences mean. … If the experience is at the center of a circle, it’s me trying to stand at every single point on the circumference of that circle to look at that experience from all angles — from the person I was when I was 24 to the person I became as a writer to meeting with the people I fought against … [to] the perspective of a Syrian activist in that country’s revolution. So in many respects the journey of the book is sort of this circular journey around this circumference and then right at the middle of it are these combat experiences.

On developing a friendship with Abu Hassar, who fought for al-Qaida in Iraq

The idea of the meeting was basically two veterans of the Iraq war sit down to talk about the war — but we fought on opposite sides. And at first I didn’t tell him that I had been in Iraq as a Marine … because we didn’t think he would meet with me. … So we sit down and we start talking. We build a rapport and … [when I eventually told] him I’d been a Marine, he sort of smiled and laughed and said, “That’s what I thought.”

That meeting was basically a bet on my part. … The experiences I had had fighting were the defining experiences of my young life — my 20s and my early 30s. And that whole time you’re fighting, it’s like a dance and you’re engaged in … let’s call it a shadow dance because your partner is someone you never see and you never meet. I had a curiosity about, you know, who I was doing that dance with? And my bet was that he would have a similar curiosity about me. And what other underlying antipathy might have existed would have been overcome by our mutual curiosity about one another.

On how he connected with Abu Hassar while Ackerman’s friend took a break from translating their conversation

Suddenly Abu Hassar and I are sitting across the table from one another and we can’t talk. We are as awkward as two 13-year-olds on their first date — kind of looking at our hands and staring around. So we started drawing this map [of the locations where and dates when they’d fought during the war]. And in that interaction what occurred to me was that this language of places and names and the dates was a language that we shared.

On going to Irbil in northern Iraq in 2014 to see the front line where Kurdish fighters were holding off the advance of ISIS

I found what I think you always find in wars when you actually go right up to the front line: You see [that] what is holding back the hordes, or keeping all civilization from collapsing, are just a handful of people with some rusty old rifles. You would think there would be a more robust presence there — but at the same time, [you’re] not surprised that there isn’t. … All that energy sort of fizzles out in the last moment and you wind up with this handful of old Iraqi fighters with some secondhand weapons who are the front line against ISIS.

On “winning” wars

I think you realize, when you look historically, that these binary concepts of winning and losing wars — it’s actually the outlier. There are just as many wars that lead to these interminable quagmires as there are wars like … the second world war which was very clear: There was a beginning, there was an end, and there was a reconstruction afterwards. But if anything, that is actually the outlier case and usually wars just sort of fizzle on.

Noah Caldwell and Jolie Myers produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Beth Novey adapted it for the Web.