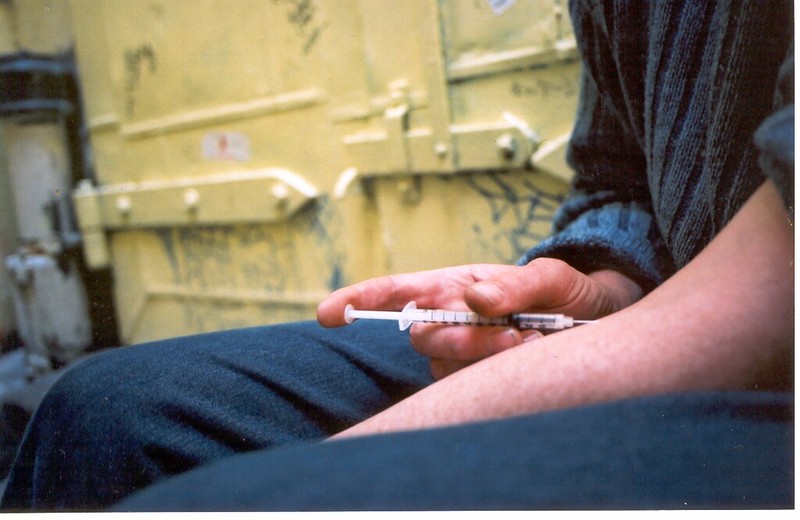

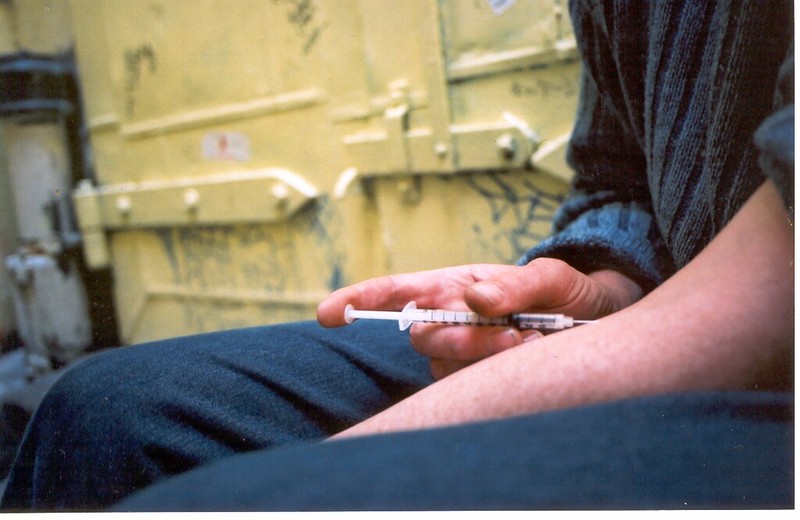

Walla Walla sees rise in overdoses

Listen

(Runtime 1:01)

Read

Last month, the number of opioid overdoses in Walla Walla spiked to 124% more than the local monthly average, according to the county’s Department of Community Health.

“It’s surprising and it’s alarming,” said Cassidy Brewin, senior behavioral health and prevention coordinator for the agency. “It’s never something I want to log onto my computer and see.”

Over the past year, Brewin said an average of about 12 overdoses have presented to the emergency department each month. In September, that number jumped to 26. Though that only accounts for officially reported overdoses, Brewin said that likely reflects a rise in non-reported overdoses, as well.

“It’s a good benchmark,” Brewin said. “But it isn’t a true reflection of the reality of the situation.”

The rise in overdoses could be connected to two new street drugs. One is carfentanil — an opioid about a hundred times more powerful than fentanyl. The other is an industrial chemical known as BTMPS.

The drugs were first detected by Blue Mountain Heart to Heart, a local nonprofit that lets people bring in their substances to see what’s in them. Blue Mountain Heart to Heart said it’s one of around 30 such drug testing sites in the country — and one of only a handful in rural areas.

Last month, the nonprofit found two confirmed hits of carfentanil. In just the past week, it’s likely found two more. The organization is waiting for confirmation from the University of North Carolina, where it sends substances for further testing.

While Brewin noted that it’s difficult to draw a direct line between the new drugs and the rise in overdoses, she said: “Anytime that we’re seeing a pretty dramatic increase in numbers, counts and percentages, that definitely gives us an indication that something out of the ordinary is happening.”

Everett Maroon is the executive director of Blue Mountain Heart to Heart. He said that he’s heard, anecdotally, about non-fatal overdoses and seizures connected to the new substances.

“If this really becomes a larger proportion of what’s in the underground drug market, we’re really facing some very dire circumstances for a lot of people,” Maroon said.

He suggested the region’s drugs could be changing because of increased restrictions on fentanyl “precursors” from China, which went into effect on Sept. 1. Maroon also said the changes could be correlated with recent drug busts throughout the Pacific Northwest.

In its testing of street drugs, his organization has found a “morass” of ingredients, including Plaster of Paris, flour, acetaminophen and xylazine, known as the “zombie drug” because of the severe wounds it can cause.

“It could be the same dealer later that week and the substance is entirely different,” Maroon said. “It’s just created a very unpredictable environment for people.”

Blue Mountain Heart to Heart also tracks the use of naloxone, a drug that can reverse overdoses. Last month, Maroon said that self-reported uses of naloxone broke the previous record by 60%.

Brewin often hears others say that naloxone is a “Band-Aid solution” — one that doesn’t solve the underlying issue. But she thinks the same can be said of other medical interventions, too.

“If somebody is having a heart attack, you bring out an AED machine,” she said. “We need to destigmatize overdoses and make sure that we’re giving people the same care and compassion that we do for any other medical condition.”

Nationwide, overdose deaths have been declining. Overall, Walla Walla County’s age-adjusted rate of opioid overdose deaths is lower than the state’s.

But official overdose deaths are tallied by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, whose reports are on an 18- to 24-month lag, according to Brewin. So, she was only able to share the county’s preliminary number of overdose deaths. In 2023, it was 14.

This year, that unofficial count has already reached 13, with three more months to go.