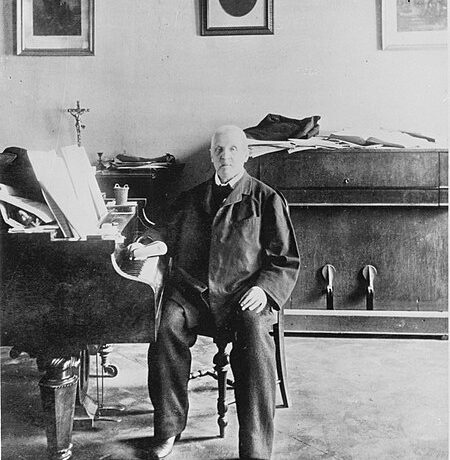

Anton Bruckner Bicentennial

“Someday I will have to give an account of myself. How would the Father in Heaven judge me if I were to follow others and not Him?”

Anton Bruckner was a humble man. A devout Catholic. A highly trained organist. A largely self-taught composer. A singular voice in music, especially in his massive symphonies.

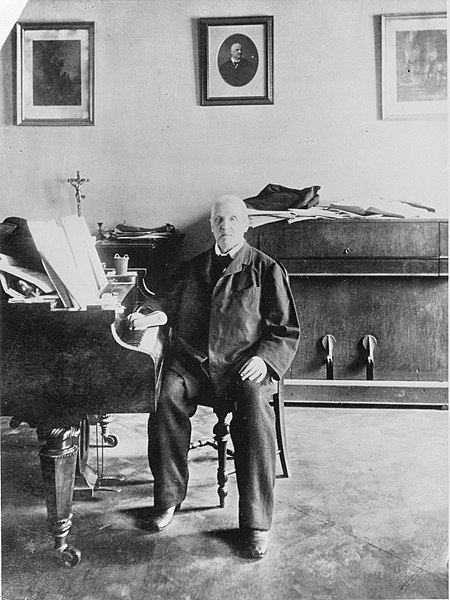

This year the world marks the bicentennial of his birth in a village near Linz, Austria (September 4, 1824). He took his first music lessons from his father, entered school at age six, and composed his first work (a sacred choral piece) at eleven. He became a choirboy at an Augustinian monastery and a regular performer on its Baroque Era organ, which he held in awe. During this time, he developed the rigorous discipline which defined his adult career, often practicing at the organ twelve hours a day. Later, he would serve as cathedral organist in Linz and court organist at the Royal Chapel in Vienna.

When he began composing in earnest at age 37, Bruckner established himself as a bold, distinctive creator of symphonic repertoire, pushing the limits of the Austro-Germanic tradition. He wrote imposing works for large forces, while experimenting with form, polyphony, and counterpoint. From Wagner and Liszt (another composer steeped in Catholicism) he inherited a penchant for harmonic innovation. He layered his orchestral scores with multiple motifs and regular repetition, even anticipating the “minimalists” of the late twentieth century.

In part because of his affinity for Wagner (several of whose operatic themes appear in his Third Symphony), Bruckner ran afoul of the influential Viennese critic Eduard Hanslick, a leader of the Brahms camp at the time. Yet the composer’s lectures at the Vienna Conservatory earned him a fair number of admirers. Gustav Mahler, for example, considered Bruckner a friend and “forerunner.”

It was not until age 50, with the successful premiere of his Fourth Symphony, Romantic, that Bruckner found any real fame as a composer. (His work as an organist had already brought him renown in Austria, Germany, France and England.) True to form, he actually tipped the conductor Hans Richter after a rehearsal of that work, telling him “Take this and drink a glass of beer to my health.”

St. Florian Monastery – the Bruckner Organ Credit: C.Stadler-Bwag/Wikimedia Commons

Bruckner’s stature continued to grow incrementally for the rest of his life. The Emperor decorated him with the Order of Franz Joseph. Upon his death in 1896 (with the last of his nine symphonies unfinished), his remains were laid to rest in the crypt of the monastery church at Sankt Florian, immediately beneath his favorite organ.

Today, two hundred years after his birth, Anton Bruckner’s music continues to challenge and fascinate. It comes at you in waves, with a wide dynamic range and resolutions without finality. It can often seem like it departs you in mid-dialogue, allowing you to pursue the ideas and emotions on your own. You don’t really hum Bruckner; you immerse yourself in it. You appreciate the blocks of sound, reminiscent of pulling out organ stops. You understand how his symphonic works have come to be called “cathedrals of sound.” In 2024, he gets his due.

Related Stories:

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Conclave

CONCLAVE: Focus Features “Without uncertainty, there is no doubt. Without doubt, there is no mystery. Without mystery, there is no faith.” Let’s face it. Without an intelligent script, talented actors

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: The Apprentice

The Apprentice: Briarcliff Entertainment When a 26-year-old Donald Trump encounters the controversial attorney Roy Cohn for the first time in director Ali Abbasi’s new film, he tells him, admiringly, “You’re

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Megalopolis

Megalopolis: Lionsgate Studios “How would you like to watch a story where nothing ever happens? In my films, everything happens.” In Federico Fellini’s utterly fascinating 1963 picture, 8½ , the