In The Mountain West, Spring Is Springing Sooner, Throwing Nature’s Rhythm Out Of Whack

LISTEN

BY NATHAN ROTT, NPR

There’s a cycle that starts when the snow melts and the earth thaws high in Colorado’s Rocky Mountains. It’s a seasonal cycle based on timing and temperature, two variables that climate change is pushing increasingly out of sync.

To the outsider, it can be hard to see: Plants still grow, flowers bud, bears awake, and marmots breed. Broad-tailed hummingbirds still trill around a landscape that evokes the opening scene of The Sound of Music, with flowery meadows and granite peaks.

But those who know this ecosystem will tell you something is a little off. The flowers are blooming earlier. The marmots are mating in early May. Spring is springing sooner across the Northern Hemisphere, changing natural cycles around the world.

In Alaska, brown bears are changing their feeding habits to eat elderberries that ripen earlier.

In California, birds are nesting and breeding a week earlier than they did a century ago.

“One of the consequences of climate change is that even though everything is happening earlier, they’re not changing at the same rate,” says David Inouye, an ecologist from the University of Maryland who has spent more than 40 years documenting the change in Colorado’s alpine meadows.

Ecologist David Inouye says he has counted nearly 5 million flowers in the meadows around the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory. He says he sometimes feels like “the Count” from Sesame Street. CREDIT: NATHAN ROTT/NPR

The results can be seen all around him. Flowers are blooming before there are bees to pollinate them. Hard frosts are still occurring long after winter’s snow melts away, decimating fruit orchards and budding plants. Allergy season is getting longer.

Inouye says that when he started spending his summers at the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory in Gothic, Colo., cataloging flowers in the thin mountain air, climate change wasn’t really a thing people were talking about. But as time went on, the evidence of it started to become unavoidable.

“Temperatures are getting warmer here,” he says. “The April low temperatures here are now about 6 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than they used to be.”

Some plants and wildlife, taking their thermal cue, have been able to adapt in kind. Some are thriving. Others are being left behind.

FEWER FLOWERS, FEWER WORKER BEES

Colorado’s snowpack this year was the worst it had been in more than 30 years. Temperatures in early spring soared.

Many researchers here view this as a glimpse of things to come.

“You can see it visually,” says Rebecca Irwin, an ecologist from North Carolina State University. “We have less flowers.”

Fewer flowers means less food for the native bees that buzz around in meadows like the one Irwin stands in.

She and two others are equipped with wispy butterfly nets and fanny packs filled with plastic vials.

They’re hoping to get an idea of how different bees are doing in this environment by catching as many of them as they can over the course of an hour. It is a task that proves easy.

Slivers of snow still hide in coulees near Schofield Pass. A low winter snowpack and high spring temperatures melted most of winter’s snow earlier than normal in Colorado’s Rocky Mountains.

CREDIT: NATHAN ROTT/NPR

At the end of the time period, it’s clear that they caught far fewer worker bees than they would have in a normal year.

“It’s hard to know if they’re just delayed or if they’re not doing well because there’s no food for them,” Irwin says.

Some bees, Irwin says, seem to be doing fine. In years like this, they’re able to emerge earlier to meet the early bloom.

“But some of them are constrained by how long it takes them to develop,” she says.

The fear is that those bees and the flowers that depend on them for pollination could slowly get pushed out.

Michael Stemkovski of North Carolina State says documenting these changes can be disheartening. “It’s kind of like watching an illness progress without having the tools to remedy it.”

WE MAY NOT LIKE THE CLIMATE CHANGE WINNERS

The ability of a species to adapt to its circumstances — to roll with the environmental punches, so to speak — is called plasticity.

Species that have a lot of plasticity tend to be generalists. They’re able to make the situation work. Species with less plasticity, those that depend on a specific ecosystem or climate, are more likely to struggle.

“When you think of a plant that can’t move over its lifetime, it either tolerates a dry area or it doesn’t,” says Dan Blumstein, a conservation biologist from the University of California, Los Angeles. He specializes in marmots, a large ground squirrel that is, in Blumstein’s words, “remarkably plastic.”

“Marmots are all about getting obese,” Blumstein says. “They adjust their annual schedule appropriately to be active when the vegetation is growing.”

An earlier spring means a longer growing season, so they have more time to gather food. As a result, Blumstein says, marmots seem to be getting bigger. He stops short of calling them a “climate change winner” though, noting that a longer growing season also means more chances for them to be killed by predators.

Other species are emerging as winners though, including “some that people might not be very fond of,” says Jill Anderson, a geneticist at the University of Georgia.

She points to poison ivy, which is expected to thrive with more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

Researchers at the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory also report seeing far more ticks this summer than in any previous year. That report is consistent with studies showing that the range for ticks is increasing with a warming climate.

And there is a lot of evidence that climate change is diminishing biodiversity, which can be seen in these alpine meadows as well.

A GLIMPSE OF THE FUTURE

Just off a ridge, in a verdant meadow, John Harte, an ecologist from the University of California, Berkeley, has created a window into the future of this place. It’s a grim one.

“When I tell people what to expect, I say, ‘Well, imagine the opening scene of The Sound of Music was filmed outside of Reno, Nevada,’ ” he says. “Because that’s what it’s going to be.”

Twenty eight years ago, Harte suspended a series of heat lamps in long, humming rows, a few feet off the ground. The lamps, which were designed for chicken farmers in Pennsylvania, raise the temperature on the ground by about 4 to 5 degrees.

“That’s comparable to the climate we expect by the year 2050,” he says.

The heat lamps have been on since then, day and night, and the change that is occurring beneath them is remarkable.

The yellow and purple flowers that dot the landscape nearby are mostly gone. In their place is sagebrush, a prolific plant that you would usually see at lower elevations.

“We are projecting that all of these meadows are going to look like that,” Harte says, pointing to the gnarled plant. “We are homogenizing the planet.”

There’s another concern, just as great. Harte and his colleagues have found that the heated soil holds far less carbon than the native ground. That missing carbon, he says, is going into the air, creating the potential for a feedback process that will accelerate climate change further.

“Ecosystems affect climate just as much as climate affects ecosystems,” he says. “And the changes happen quick.”

Copyright 2018 NPR

Related Stories:

Thousands of salmon eggs arrive at southeast Washington schools

Sarah Moffitt, education coordinator for Tri-State Steelheaders, pours salmon eggs into a tank at Davis Elementary School. (Credit: Susan Shain / NWPB) Listen (Runtime :59) Read It’s “egg day” at

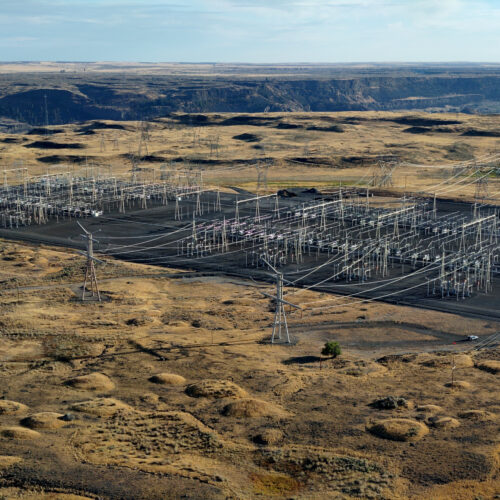

This transfer will help Grand Coulee Dam run more efficiently, save money

One of the electrical switchyards at Grand Coulee Dam. (Credit: Bureau of Reclamation) Listen (Runtime 0:56) Read There’s a transfer happening at Grand Coulee Dam. After years of planning, the

To help cool the Tri-Cities, kids plant hundreds of trees for cooler parks, playgrounds

Elena Woodford and Alexis Nicholson help plant one of seven trees at Tapteal Elementary School. Alexis co-founded the Kids for Urban Trees club to plant trees in the community. (Credit: