COVID is far from over for some Latinos

Listen

(Runtime 5:21)

Read

The Yakima Valley was one of the hardest hit regions in the country during the COVID pandemic. Now, Hispanics and Latinos in the area are still dealing with symptoms.

This is part first of a collaborative piece with palabra, the National Association of Hispanic Journalism media outlet, about Long-COVID.

Maria always thought of herself as the healthiest in her family. As an active Hispanic in the Yakima Valley she lived a normal life, dedicated to her children and her work for the community. She said COVID changed all of that.

“On January 1, 2021, I woke up sick. I felt very tired, I felt cold,” she said in her native Spanish.

Maria chose to not use her full name in this report. She said everything she has been through makes her very anxious and emotional. She said she didn’t think it would be so hard to talk about what she has experienced in the last few years.

“I couldn’t even get up to drink water. It was something strange, strange in my body. I went 10 days, 15, until I had 21 days without sleep,” she said the she doesn’t know how she survived it.

At that point, she said everything was very confusing for her. She doesn’t remember how she confirmed her COVID infection but she thinks she got a test.

Maria was one of hundreds of Hispanic and Latinos in the Yakima Valley infected with COVID.

The Yakima Valley became one of the COVID hotspots on the west Coast. Several outbreaks erupted in jails, nursing homes and at agriculture and food processing facilities.

Life for many infected by COVID slowly returned to normal over the next few years. But not for Maria.

She thought her symptoms would pass, but for her – and so many others – COVID came to stay.

“I continued with the same symptoms: extreme tiredness, aches and pains from head to toe. I felt extreme inflammation,” Maria said.

Looking for answers

Maria said she visited her doctor each week. She said she tried the different treatments prescribed to her, some of which caused side effects.

She also recalled an emergency room experience in 2021. She said she went to the ER because her fingers suddenly turned purple.

“The woman from the emergency room wanted to clean my fingers because she thought it was paint. I told her, ‘How do you think I’m going to come to the hospital because I have painted fingers?’ That is illogical,” said Maria.

Doctors in Yakima gave her different diagnoses — carpal tunnel syndrome, multiple sclerosis or that she needed a hip replacement.

She said she never had those health issues before.

“I felt like no one understood me,” she said, even when she said she insisted that everything started after she got COVID.

The burden was not only emotional, it was also financial.

“I don’t have insurance. That’s another difficult thing. I have spent a lot of money but for health it doesn’t weigh me down,” she said.

Maria said she remembers that one of her lab bills exceeded $1,000. She said she and her husband have managed to cope with the expenses.

Then, in March 2022, her primary doctor referred her to a rheumatologist in the Tri-Cities, who finally had an answer.

“When I talked to the doctor, I got so much off my chest. She told me, ‘There are so many people like you. You’re right, it’s not in your mind. Yours is a Long-COVID patient [case],” Maria said.

What exactly is Long-COVID?

Doctor Leo Morales is the co-director of the University of Washington Latino Center For Health. He describes Long-COVID as longer-term complications of having had COVID.

“It’s a multi-system, multi-organ impact that results in various kinds of symptoms like fatigue, brain fog, loss of smell, changes in sleep and many other symptoms that emerge out of this condition,” he said.

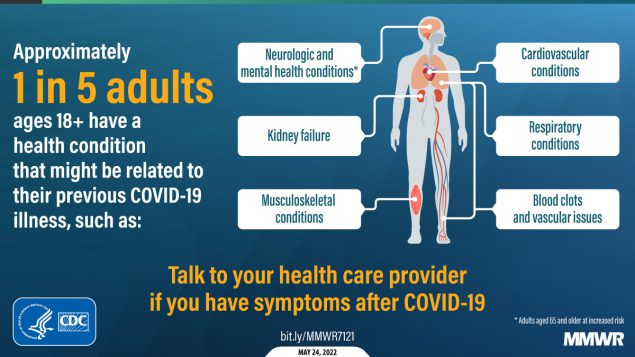

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website defines long-COVID as “signs, symptoms, and conditions that continue or develop after acute COVID-19 infection.”

A graphic from the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) shows health conditions that might be related to previous COVID illness. (Courtesy: CDC)

The CDC also noted it goes “by many names, including Post-COVID Conditions, long-haul COVID, post-acute COVID-19, long-term effects of COVID, and chronic COVID.”

Doctor Tao Kwan-Gett, Washington’s Department of Health Chief Science Officer, said Long COVID is serious, but he also said it’s hard to know how many people are affected.

“It can sometimes be difficult for people with long COVID because the symptoms sometimes don’t have a visual manifestation. Sometimes you can’t see the symptoms,” Kwan-Gett said.

Morales and Kwan-Gett both said that there is no test or exam that can provide a diagnosis.

Kwan-Gett said in Washington, health care providers and laboratories aren’t required to report Long-COVID cases.

“There are many conditions where reporting individual cases is helpful but there are many diseases where reporting doesn’t really help us prevent the disease and long COVID, I think, is one of those where we don’t have a way of directly counting every case,” he said.

As of October 2023, the Washington State Department of Health (DOH) “estimated 6.4% of all adults in Washington state are currently experiencing long COVID, with 95% confidence that the true number is between 5.9% and 6.8%.”

The DOH also “estimated 117,000 Washingtonians are experiencing significant activity limitations, with 95% confidence that the true number is between 67,000 and 182,000.”

According to the DOH information, provided by email, “the relative prevalence of long COVID is higher in Eastern Washington than Western Washington.”

These estimates come from a project conducted by the Centers for Disease Control Epidemic Intelligence Service officer assigned to Washington State. The study did not specify ethnicity or race.

According to DOH, the research uses mathematical models based on the number of cases and hospitalizations to estimate the number of Long-COVID cases that would be expected from these infections.

“This is a new model that needs further refinement and validation. So, it is not a regular part of our surveillance system that is updated regularly,” it noted.

Still, different studies locally and around the country show that Latinos are among the most affected by Long-COVID.

This report is a collaboration between Northwest Public Broadcasting and palabra, the National Association of Hispanic Journalists multimedia platform.

NWPB’s Johanna Bejarano worked with Lygia Navarro, a journalist with palabra. This is the first in the series of collaborative pieces about Long-COVID in Central Washington