Camille Patha trades bright, bold colors for dark, evocative journey into black

Listen

(Runtime 1:13)

Read

Editor’s note: This story contains language that may be offensive.

Two days before Camille Patha’s exhibit, “Passion Pleasure Power” opened at the Tacoma Art Museum, the artist walked around the gallery, a space filled with some of her new works from the past three years.

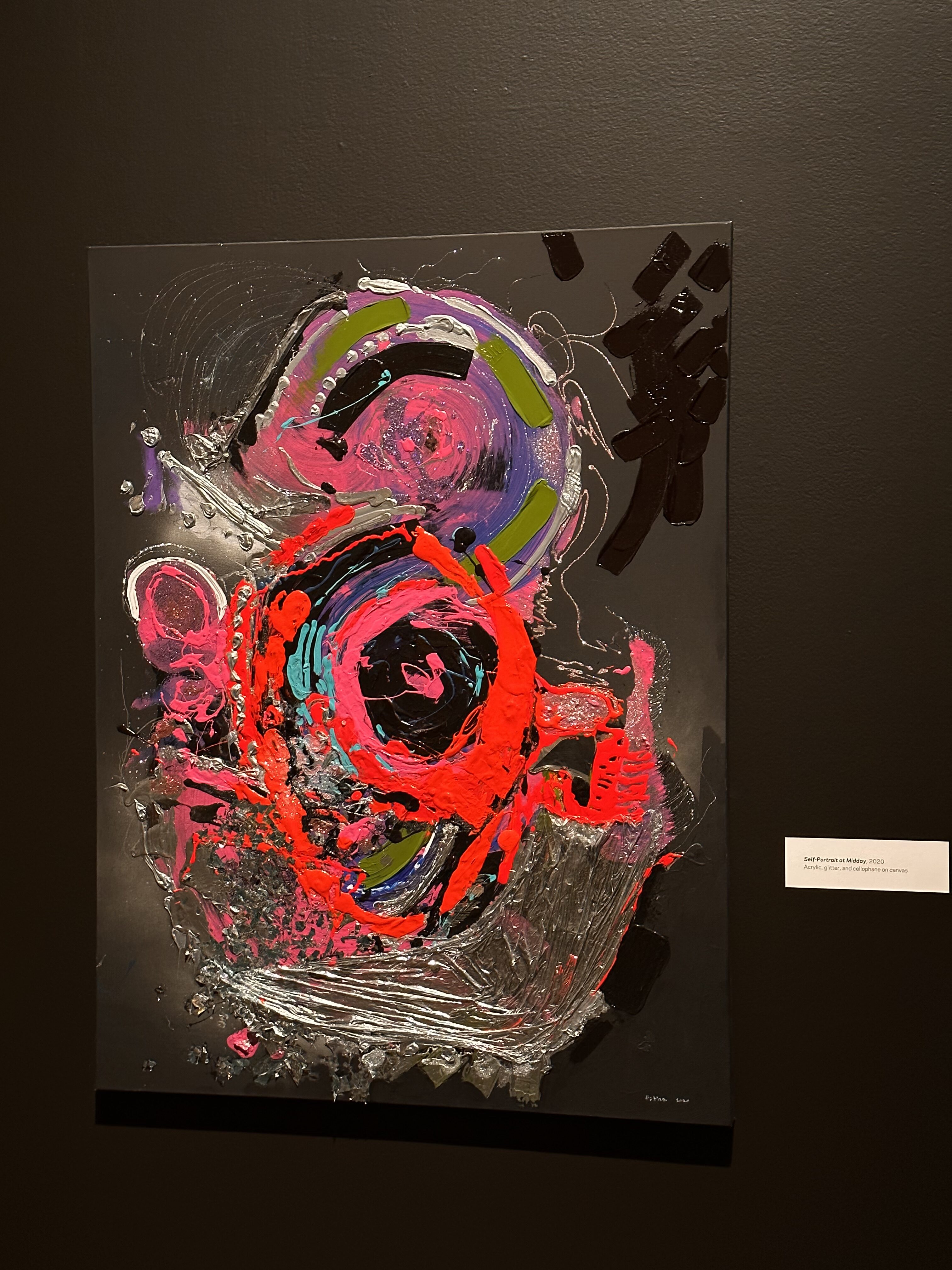

From a bench in the exhibit, she pointed to her favorite piece, a self-portrait on black, titled “Self-Portrait at Midday.” Made from acrylic, glitter and cellophane on canvas: bright pinks and reds swirl around each other, layered over the black canvas with an even deeper black popping up and over them. Silver cellophane, paint and glitter add flourishes to the round shapes and some greens, blues and purples are layered within the curves.

“Self-Portrait at Midday” by Camille Patha. (Credit: Lauren Gallup / NWPB)

“It’s perfect,” Patha said, looking at the painting. “Now let’s talk about black. If you look at the background, it’s kind of a nice, almost a gray-black. But if you put black with it, it’s a gloss color, you can streak it out there. It’s a different black entirely, it’s much deeper.”

Looking at art in a museum exhibit with the artist is a rare experience. Most visitors to Patha’s new exhibit won’t get to view the art alongside the artist — but they’ll come pretty close. A short documentary profiling her, “Camille in Color” created by filmmaker David Wild, plays on a screen in the gallery.

“I make paintings because — they’re waiting for me,” Patha said in the documentary.

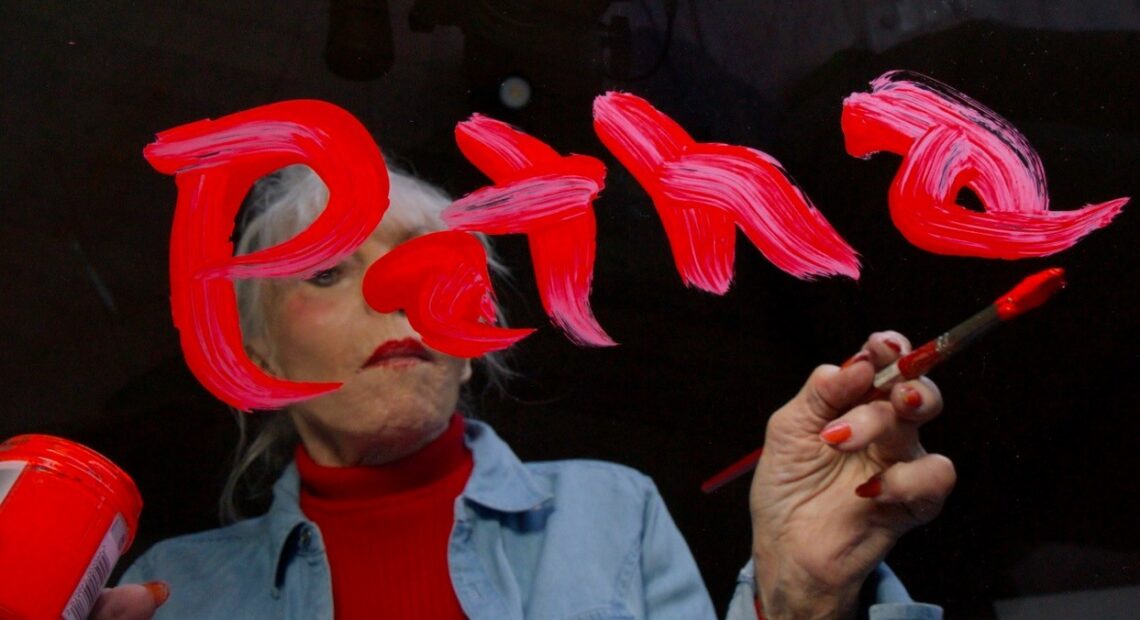

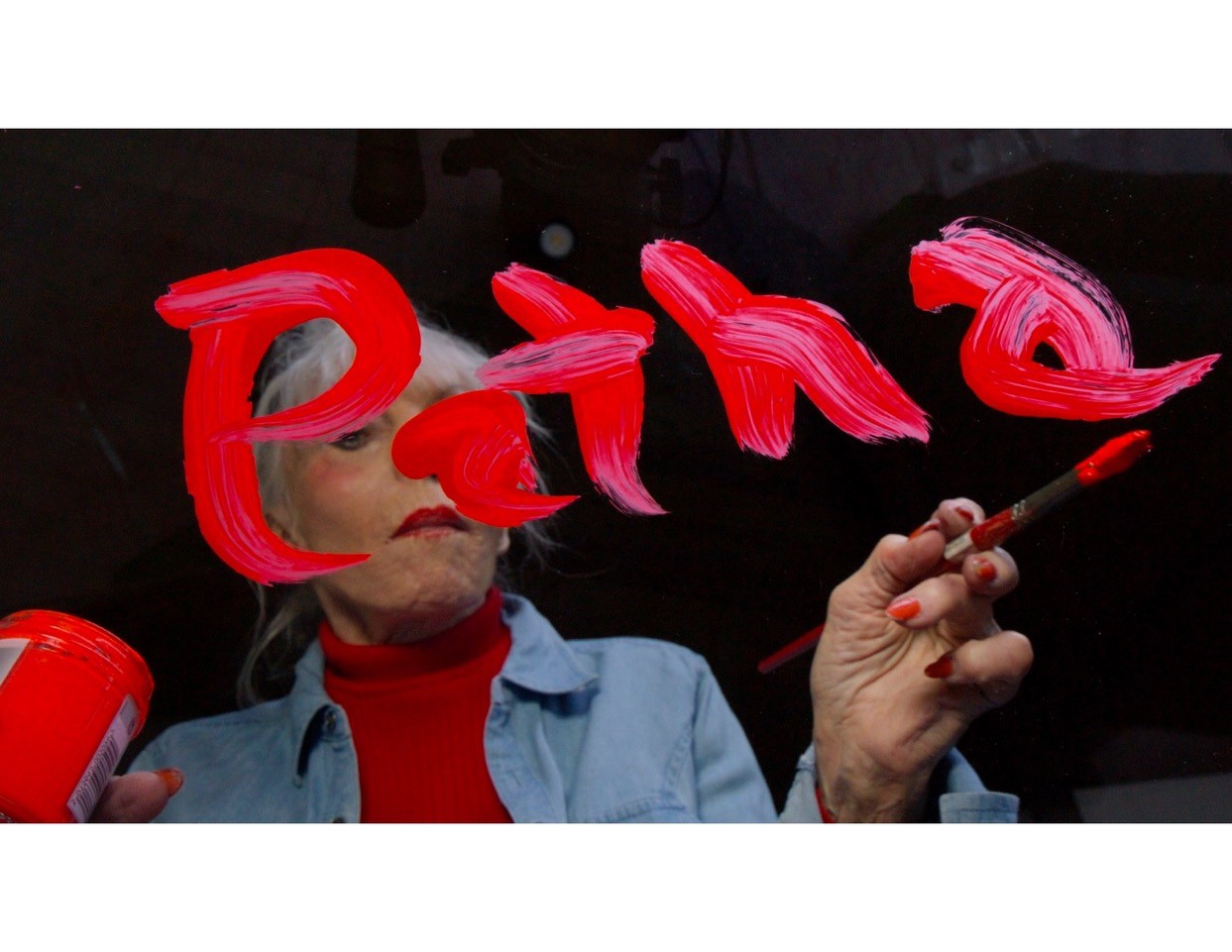

A still from the documentary, “Camille in Color” by David Wild. (Courtesy: The Tacoma Art Museum)

Patha has spent her life not waiting. She’s been making art since she was a kid, when her mom gave her some crayons and colored pencils to keep her out of trouble. She married when she was 17 and moved to Arizona, where she studied art at Arizona State University.

In an essay titled, “Power and Paint: The Art of Camille Patha” Rock Hushka writes about how the hot, dry state of Arizona awakened Patha’s use of color. That eye for brightness was discouraged when she moved back to Washington and earned a bachelor’s degree and then a master’s degree at the University of Washington.

“Patha was challenged during her time in graduate school. Her painting style and color palette were neither embraced nor encouraged by most of the UW’s painting faculty. Patha describes the experience as traumatic,” Hushka wrote.

-

- Museum attendees are greeted by this piece, “Moonstruck” when they first enter the space. This work is composed of fabric, glitter and mirrors on canvas. (Credit: Lauren Gallup / NWPB)

-

- A gallery collection of paintings, pastels and acrylics in the exhibit. (Credit: Lauren Gallup / NWPB)

-

- The collection of new works from the past three years is meant to capture emotions and sensations one can’t see. (Credit: Lauren Gallup / NWPB)

But the bright, bold and hot colors stayed and became Patha’s signature, and the Pacific Northwest fell in love with her for it.

The Tacoma Art Museum, where this current exhibit is housed, is just one of the Northwest museums that recognized her pioneering talent. She was exhibited in Seattle Art Museum, Bellevue Art Museum, and the Otto Seligman Gallery soon after graduate school in the 1960s and has been in countless art institutions over her 50-plus year career.

Of course, a signature can change. While known for her use of bold, bright colors, this collection of paintings turns to a darker yet still bold choice: black.

Labeling Patha is an exercise in futility. She’ll tell you so herself.

“Why did they call it women’s art? Jesus! That makes me mad,” Patha told the crowd in her opening remarks speech. “I’m not a woman artist. I’m an artist.”

While artists can get pigeonholed into identities and genres, even by museums that expect them to maintain a certain style, Exhibit Curator Faith Brower said she and the museum welcomed Patha’s evolution in this new exhibit.

“We understand her history as an artist, her style as being that punch of color, that vibrancy. And I think you’re all going to see pretty easily when we go up into the gallery what floored me about her new work,” Brower said during the opening remarks.

“No Ordinary Love Song” is one of the mixed-media pieces in the gallery, composed of acrylic, mesh, fabric, glitter and coal on canvas. (Courtesy: The Tacoma Art Museum)

When she visited Patha’s studio to curate the exhibition, she expected to find the “colorful, punchy abstract paintings” Patha is known for, Brower said. Instead, she found work that she described as dark, bold, evocative and, “pushing the boundaries of painting.”

“She’s more than a single definition would allow for, and that’s exciting for me as a curator,” Brower said. “I love to see how an artist’s style and career can change and evolve with time.”

This new exhibition centers on black, a gorgeous, deep, matte black that Brower said provides a luscious backdrop for the work.

“If you’re into color and understanding Camille’s own passion for color, then I encourage you to explore black as a beautiful, wonderful color that it is,” Brower said.

The exhibition might take Patha fans down a new path with its diversion into the world of black, but it certainly remains true to Patha’s core at being able to paint what we cannot see.

“So much of the work that Camille has made over the last few years is work that explores things that are not typically visible to us. They’re feelings, they’re emotions, they’re passion, they’re pleasures, they’re touches, they’re sentiments; the things that we have a hard time using words to describe,” Brower said.

The exhibit is a collection of two-dimensional paintings, pastels, acrylics and large mixed media pieces. Some of the sculpted, three-dimensional works evoke painting mechanisms by wrapping fabrics into patterns and lines that mimic the patterns and lines in her two-dimensional pieces, Brower said.

Patha described the work as sensual, but pointedly not erotic in theme. She makes an effort to articulate her meaning in the pieces quite clearly. So much so, that she revealed during her opening remarks that she’s bothered by being called an abstract artist.

“What do you mean abstract? It’s not abstract,” Patha said. “It’s real. It’s very specific.”

Patha uses elements of art, color and space with intention to communicate as an artist.

“I change a column, I change the shape until it’s just right,” Patha said, comparing her work to how an engineer solves a mathematics equation.

She described paint as another language with which to communicate. When asked if the “words” she has used to communicate through this language of paint have changed over her career, she said they probably have.

“I was treated as an abstract expressionist. It was good, really good, gorgeous,” Patha said. “But it was just not as internal as this stuff.”

Patha works at night, so she won’t be interrupted, she said.

In the exhibit, collections of painting and acrylics like, “Night Thinking,” “Oceans” and “The Pulse Paintings” hang on the gallery walls, alongside pieces that stand on their own.

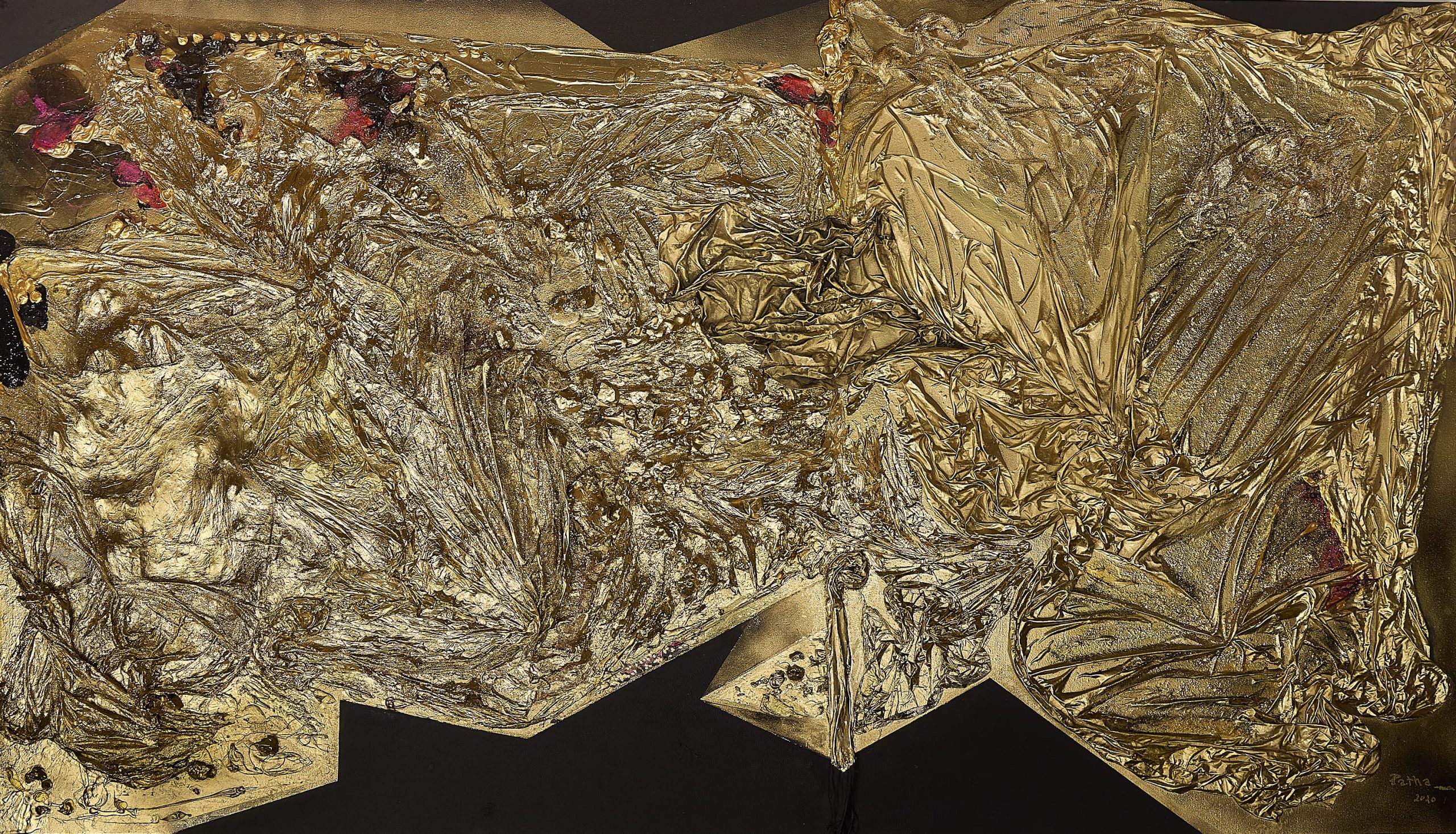

The sculpture, “Thrill” is composed of cascading gold fabric layered over three pentagonal canvases, evoking the shape of a woman draped in cloth. The exhibit label describes the sculpture as reminiscent of Marcel Duchamp’s 1912 “Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2.”

“Thrill,” by Camille Patha. (Credit: Lauren Gallup / NWPB)

The exhibit label for “Night Thinking” encapsulates Patha’s journey into black:

“In Patha’s ‘Night Thinking’ series, it is as if each painting reveals when a star is born or dies, or an Aurora Borealis, also known as the Northern Lights. With this in mind, these paintings are both abstract and representational. This paradox is just one of the many strengths of a Patha painting, as there is often more than meets the eye.”

“Passion Pleasure Power” is on display through Sept. 3 at the Tacoma Art Museum.