Past As Prologue: The Non-Coastal Inland Northwest’s Big Ties To The Ocean Shipping Industry

Listen

NOTE: The following essay and its audio component are part of an ongoing series produced in conjunction with the Washington State University history department. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

BY KAREN PHOENIX

Before 1956, if you were going to ship goods, they had to be loaded onto a railcar, truck, or ship essentially by hand—an incredibly labor intensive and expensive process.

If you were shipping by sea, the process went like this: At the shipper’s factory or warehouse, freight would be loaded piece by piece onto a truck or railcar. They would then deliver these hundreds or thousands of items to the waterfront, where each was unloaded separately, recorded on a tally sheet, and carried to a storage or warehouse. When the ship was ready to load, the process was reversed (it was kind of like when you move houses, and everything is packed, loaded and unloaded by hand).

This work was physically demanding, as longshoremen carried goods into the cargo hold by hand: 80 pound stems of bananas were walked down a gangplank, and coffee came in 120 pound bags. Reloading the ship could not take place until every bit of cargo had been unloaded. The work was highly irregular. One day, the urgent need to unload perishable cargo would create sudden jobs, with little work the next day.

Malcolm Purcell McLean, who owned a North Carolina trucking company, was well aware of how expensive shipping was, and he tried to come up with a solution. His ideas included having ramps where men could drive delivery trucks onto the ship and then deposit their trailers. This morphed into having just the trailer bodies, but those had to be manufactured. Small steel boxes were available, but they were generally too small to be practical; truck trailer bodies were also available, but they were too heavy.

McLean contacted Spokane resident Keith Tantlinger, who had a reputation as a container expert. Tantlinger designed a 30-ft aluminum box that could be stacked 2 high on ships going up and down the Atlantic seaboard, and on the barges operating between Seattle and Alaska. After the ship reached its destination, they were easily placed on a chassis pulled by a truck.

This invention of the shipping container reorganized the world’s economy. At a local level, factories and warehouses moved farther from the docks as transportation costs dropped. Without the need for people to physically move goods, the numbers of longshoremen dropped in some places by 90%. And, as our recent experience demonstrates, since distance between producer and consumer was essentially no longer a factor, many companies moved factories abroad where labor costs were cheaper.

The development of container ports—who could afford them and where they were located—also had consequences. The cheapness of shipping, and the global shift of manufacturing to Asia, caused a boom in port constructions on the West Coast. Seattle, Oakland, Los Angeles and Long Beach were the winners in this contest, and older ports like Portland declined. In the 1950s, Portland handled nearly as much cargo as Seattle, but couldn’t muster the money or resources to build a container port. The consequences were dramatic. Seattle’s foreign trade doubled between 1963 and 1972, while Portland’s barely grew.

The global trade network that we have today is largely thanks to Tantlinger’s containers, but there are some substantial drawbacks. The increasingly large size of ships means that they stretch existing transportation infrastructure like the Suez and Panama Canal (both of which were built to handle much smaller ships). Container ships also produce large amounts of greenhouse gasses. In 2009, the largest 15 ships emitted as much greenhouse gases as 760 million cars—or about two cars for every American. Plus, their size and distribution of weight can leave them vulnerable to capsizing or losing containers in rough seas, as Marketplace recently reported.

Related Stories:

Past As Prologue: Gendered Epithets In Pacific Northwest Politics And Beyond

Past as Prologue essay about gendered epithets in Pacific Northwest politics and beyond.

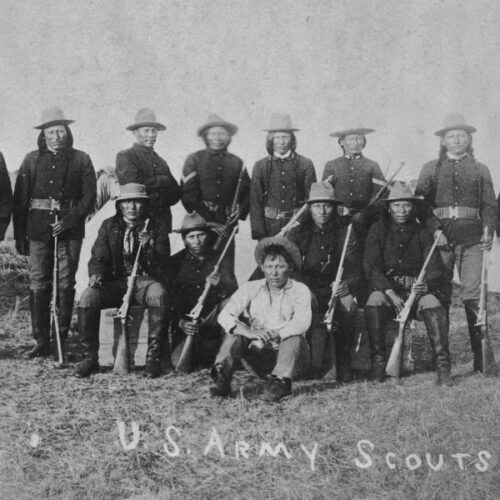

Past As Prologue: The Complicated Relationship Between Indian Scouts And The U.S. Government

The story of some Native American Scouts and their complicated reasons for working with the United States government.

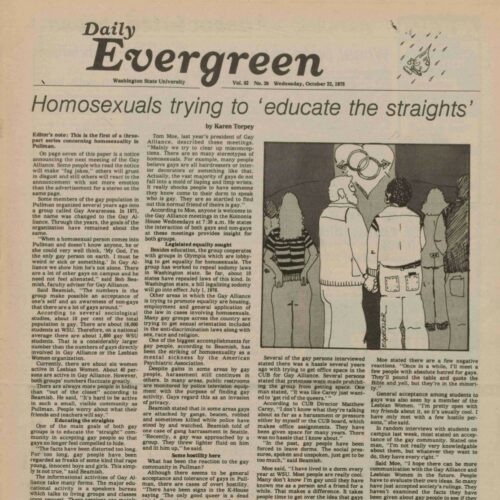

Past As Prologue: Rural Places Are Queer Places And The History Of WSU’s LGBTQ Awareness

What the struggle over recognition for WSU’s Gay Awareness student group shows is some of the similarities between rural and urban LGBTQ rights. Rural areas — especially college towns like Pullman or Moscow — are also queer places. People in cities who were against gay rights used the same tactic as those in Pullman—the public-referendum—to deny housing or employment equality to LGBTQ people.